A beautiful existence or a full life?

The invisible tradeoffs of living abroad. Or going "home."

“The loneliness of the expatriate is of an odd and complicated kind, for it is inseparable from the feeling of being free, of having escaped.”

- Adam Gopnik, Paris to the Moon

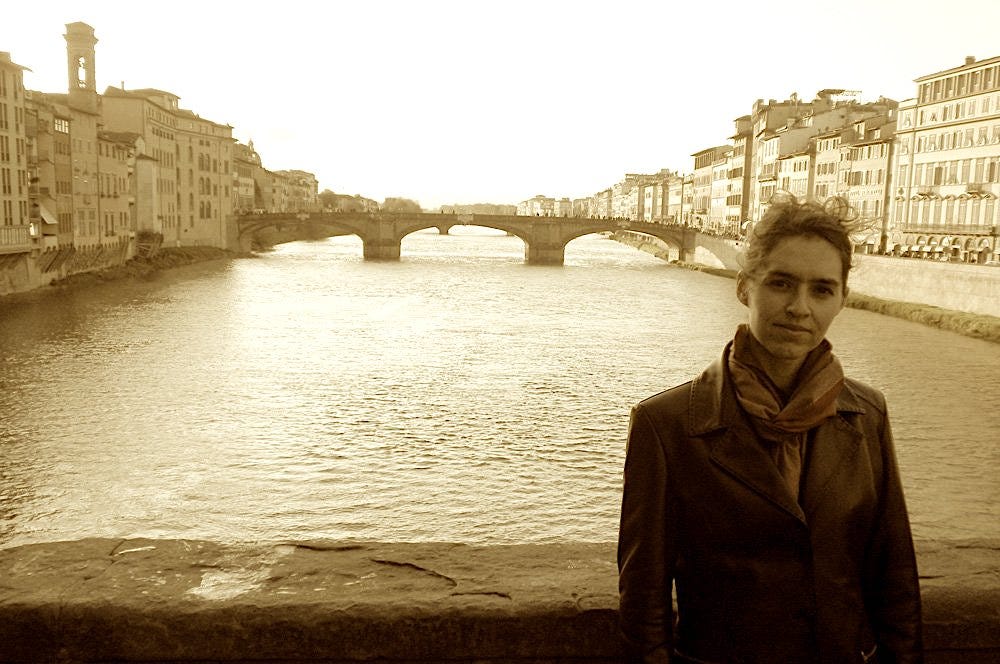

A million years ago (or maybe closer to sixteen), I was in my twenties with a baby and a toddler. My husband and I had been married almost five years, and we were on our first starry-eyed attempt at moving to Italy.

We lived in an upstairs apartment in a little town on the edge of the Piemontese alps. The furnishings were uninspiring, but you could hear the church bells from our open window. And high up on the hill were the ruins of a sixteenth-century castle bombed by the Nazis during World War II.

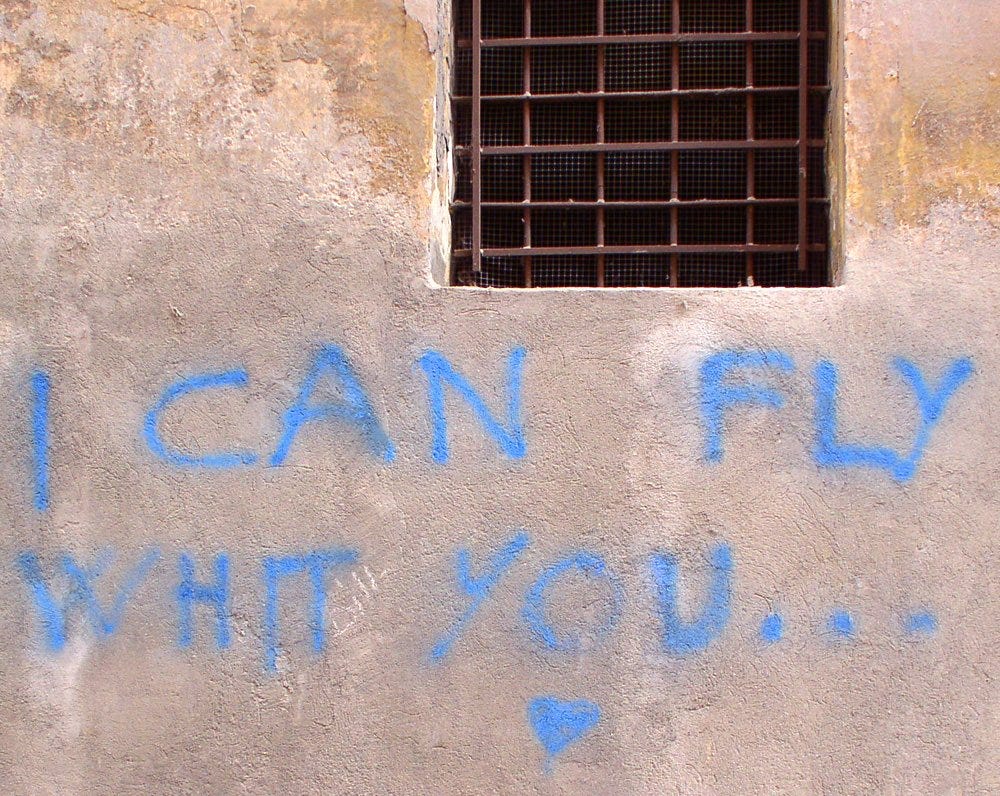

All the graffiti on the walls in Italy sang of love.

But I say “first attempt” for a reason. That brief time in Italy felt like everything I’d ever dreamed, but it lasted less than a year. We had so much to learn. “Digital nomad” wasn’t yet a term in my vocabulary back then, and I didn’t know anyone else who had moved abroad so young and in such a precarious way.

There were the diplomats, of course, and expats relocated for high-flying jobs. I’d heard of military families, missionary families, teachers at international schools. The thing everyone seemed to have in common was that they belonged to some kind of institution, and that’s how they’d managed to propel themselves Elsewhere.

I didn’t have a name for people like us, who just wanted to move abroad, and were desperately trying to find a way to make that dream possible. And I also couldn’t find any real models for doing it as twenty-somethings with small kids and without established careers, let alone savings.

Which didn’t stop me from looking. Between Kafkaesque trips to local government offices to process my husband’s citizenship (and therefore our right to stay in Italy), I searched for guideposts, a map to moving abroad, or maybe just someone to understand.

The only models I found were ones like Under the Tuscan Sun, or A Year in Provence, about midlife reinvention in southern Europe. But the protagonists of these books were in their forties and fifties, and moving without kids. Though their lives abroad might be challenging, none of those challenges had to do with diapers or preschool or kids not sleeping through the night.

Then I discovered Adam Gopnik’s Paris to the Moon. In 1995, The New Yorker invited him to move his young family to the City of Lights. What a fantasy come true! To say that I hung on Gopnik’s every word would understate the effect this book had on me. His life was the stuff of my wildest dreams.

He did indeed move to Paris, and spent five years sending back erudite essays to The New Yorker. Then he published those essays as a bestselling book. The glamour clinging to Gopnik’s life was only heightened by my sense of imagined kinship: he had two small children, just like me, and wrote with humour and tenderness about the joys and challenges of everyday family life abroad.

Of course, even in the late 2000s when I discovered Paris to the Moon, it evoked a vanishing world. Not least of which the fact that Gopnik’s reality was one where a magazine would pay someone to live in Paris for five years and send back the occasional missive.

But the environs in which he wrote were different too. Cell phones weren’t yet a thing. TikTok sandwich shops were decades in the future. Recalling Paris to the Moon now, a quarter century on (it was published in 2000), I’m struck by how much closer it feels to Hemingway’s Paris than our own.

Still, at the time, it was possible to convince myself—if mostly through sheer wishing—that Gopnik and I had much in common.

It came back to the fact that his years in Paris were spent in the throes of early parenthood. The book strolls from philosophical café conversations to afternoons in Luxembourg Gardens with his kids. I read it breathlessly in our tiny apartment in northern Italy, and tried to convince myself my life was—and would become ever more—like his.

And in a way, it was true. The things I loved most in Gopnik’s book were the little ones: intimate details of his life in Paris. Many, I related to—the moments of cultural disconnection, the Napoleonic bureaucracy that France and Italy share. The surreal feeling of seeing your toddler so at home in a place where you still feel foreign.

Most of all, this:

“The hardest thing to convey is how lovely it all is and how that loveliness seems all you need.”

Yes, that was exactly how I felt. I was always trying and failing to explain my all-consuming desire to move to Italy. How can you say you’re moving somewhere just because it’s pretty?

But I was. Back then, I barely knew about universal healthcare, permanent contracts, or the social safety net. No one was more surprised than I when moving to Europe improved my life in every possible practical way.

I don’t always admit this, but it’s true: I did move here for beauty. Because it made a difference to me what was in the background of my life. I guess I had some intuition that given a chance, setting could become character.

So often, Americans seem to think of beauty—when they think of it at all—as a frothy extra; a “nice to have” or something only the rich deserve. In Italy, and so many other places in Europe, beauty is something you breathe in with the air. A cappuccino in a piazza. The curve of a Roman ruin. Flowers in window boxes, leaning out over cobblestones.

Not everyone seems to notice it, or care, but for those with an inborn thirst for beauty, it can quickly become a necessity. Like air. A reason you can’t imagine going back.

Gopnik seemed to agree with me on this, and made the sentiment sound reasonable. Inevitable, even. I revelled in the elegant way he said everything I felt. In fact, I was so caught up in the enchantment of Paris to the Moon that the end of the book took me completely by surprise.

There we are, on the final page, rhapsodising over fairytale lights on the Eiffel Tower. Then Gopnik casually mentions they are moving back to New York.

I was flabbergasted. Incredulous.

Why in the world? If you loved Europe the way he did (the way I did), why would you leave?

Looking back, I suspect that their return might have had something do with the end of the The New Yorker footing the bill.

Gopnik, though, says something else:

The forces drawing us home were pretty strong and even pretty attractive: We wanted Luke to go to a New York school, for one thing.

"We have a beautiful existence in Paris, but not a full life," Martha said, summing it up, "and in New York we have a full life and an unbeautiful existence."

And there it was. The question leaped out and grabbed me by the throat.

A beautiful existence or a full life?

A beautiful existence or a full life?

It kept drumming inside my head, long after I closed the book. I’m still thinking about that question now, nearly two decades down the road.

A beautiful existence or a full life. What in the world did Martha Gopnik mean?

The beautiful existence part I got immediately. It’s what I was always after, what I’ve found. In fact, I find it anew every day when I step out my door and see a row of canal houses or light-drenched square or palace turned art museum. Sometimes it’s so good, I feel almost guilty. Who am I to deserve such generous, unrelenting beauty?

Then I think of the opening page of The Secret History, and wonder if it’s what’s going on with all of us—with us Americans who move abroad.

“Does such a thing as 'the fatal flaw,' that showy dark crack running down the middle of a life, exist outside literature? I used to think it didn't. Now I think it does. And I think that mine is this: a morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs.”

A morbid longing for the picturesque. A beautiful existence. Is there something wrong with us for wanting that? Something fatal, even? Is this beautiful existence somehow mutually exclusive with whatever constitutes a full life?

I feel a certain urge to jump in here with a peppy “No!”

I’ve lived abroad (this time around) for a decade now. The whole premise of my life is that of course it is possible to have it all, to live a full life in the midst of a beautiful existence.

And yet. People I know keep moving back to places they regretfully say are less beautiful than here. And far more people never move abroad at all. Even the ones who tell me, “I would love to move to Europe.”

Something is obviously going on.

No doubt some of the reasons are logistical or financial. Visas. Jobs. Family responsibilities. But even accounting for all that, I think there might be something more. While reading Gopnik’s book, all I wanted to think about was a beautiful existence. But the ghost of a full life nagged at me too.

What is a full life? What am I in danger of giving up in my headlong pursuit of beauty?

I suppose what makes up a full life must be intensely individual. Everyone’s different, with different longings and desires. But I can repeat some reasons people I know have cited for moving back. They’re the kinds of things you might expect: friends and family; community in general. Professional satisfaction, or progress in a career. Deep knowledge about—and full participation in—civic and cultural life. Connecting one’s children to their roots.

These things aren’t small, and they’re not simple either. It’s not impossible to find them abroad, but it doesn’t happen instantly, or without a lot of work and luck. For some, it doesn’t happen at all. Or they manage one or two, but ultimately feel the missing piece is too big to do without.

There have been many things I’ve done without. Though perhaps my secret was deciding to leave young enough that—unlike the Gopniks in New York—I hadn’t built a full life yet. Maybe I thought I didn’t have much to lose, so I might as well start trying to build a full life abroad.

Still, spending my first decade of adulthood in constant motion, and the next in an international city (transient as such cities are), I’ve made and lost more friends than I can count. “Lost” in many senses. Some I’ve lost touch with completely, through lack of effort, consistency, or social media in common. With others we’ve simply drifted into distance, while still “following” the broad outlines of each other’s lives. Still others remain close in spirit, though our paths have diverged across oceans and we see each other rarely, if at all.

And yes, my unimpressive career trajectory probably has something to do with being raised as a future Mormon housewife. But flitting around the globe in my twenties certainly can’t have helped. My husband has leveraged our international life into a good job at a multinational company; but he’s made plenty of career sacrifices too.

I’ve lost innumerable hours I could have spent at family dinners, getting to know my nephews and nieces, building friendships with my siblings as adults. My kids connect with their grandparents and cousins mostly through text messages and the occasional Zoom call. And the even more occasional Transatlantic pilgrimage.

In fact, I think a lot about my children. For them, these losses are not volitional. They don’t participate fully in their native culture; they’ve grown up on the other side of the world from everyone they’re related to. I hope I’ve given them something too: deep knowledge of another way of life, a sense of the vastness of the world. But will they think it’s worth it in the end?

I hope so, but I don’t know.

I take none of these losses lightly. And when I stack them up on one side of the scale, they’re monumental. It beggars belief that I’ve given all that up. And for what? Sunrise in Prague? A bicycle commute to the Rijksmuseum Library? A bookshop in Italy?

At what price beauty?

(What kind of monster am I?)

And yet. That picture, too, is incomplete. I can’t escape the simple truth of it: I’m happy here. I’ve built a community in Amsterdam, and then built it again when everyone moved away. This international life has thrown me into the orbit of people I’d never otherwise have met. My circle of far-flung friends is a cornucopia of perspectives, nationalities, adventurous souls that enrich my life.

In each place I’ve moved to, I started out laughably uncultured, lacking the most basic of shared references. More than once, I’ve stumbled through election day in a foreign country, still trying to grasp which parties stood for what. But acknowledging these deficiencies opened me up, pushed me to learn, to absorb, to examine each new thing in a dozen different lights.

Daring these things has made me who I am.

And then there’s beauty.

Somehow, I never become inured to it. The moon rises over the canal, and it’s like falling in love for the first time. I taste a new cheese with a new wine, and the whole world is new. I ride through Vondelpark at midnight with the wind in my hair, and the opera I’ve just seen crescendoing in my ears, and I think, there’s nowhere I’d rather be than here.

Have I chosen right, then?

Have I chosen wrong?

Does the question even have an answer?

I’ve traded away the unthinkable. I’ve been gifted richly in return.

Is it worth it? Is it enough?

Don’t we all make concessions in the end? Don’t we all give up one thing, hoping for another? At least once in our life—whether we leave our home town or not—don’t we make that one choice that changes everything?

There are no guarantees, and no do-overs. There’s just today, every day, and a world of ever-narrowing choices.

Yet are they really narrowing? Maybe the choices left to us are different than what would have been. But maybe the road is infinite in all directions. Every crossroad leads to another. Each road taken leaves other roads behind, but opens new vistas ahead. Maybe it’s only after the leap you see the view.

A beautiful existence or a full life?

Are they really in opposition?

I’ve come late to the understanding, but I’ve come; a full life—for me—encompasses a beautiful existence. I can’t imagine one without the other. I can’t understand either of them apart.

Beauty is my north star, the bright sun by which I see all else. When I follow that star, my life is full.

And for you? Well, only you can answer that.

(a part from my sour restack - which has nothing to do with you and more with the fact that I feel rejected by my homecountry) I like your perspective. I fell in love with Melbourne because waking up with the backdrop of a big city with modern history makes me feel like I am part of something bigger, and it fills me with pride and makes me thing ' yep, that's exactly where I want to be' and while most people dreeeeeam of Italian holidays, I don't need a holiday because I am living my dream everyday. We are lucky!

Thanks for sharing this wonderful story. In our early thirties, my wife and I had the chance to take my company up on a transfer from Arizona to Australia. I had always wanted to go there and all of a sudden we were holding permanent residence visas and were flying to Melbourne. Shortly after our arrival I was moved to Sydney.

We loved it there. For us Australia was beautiful. It was like the US but very different. Then we were hit with that full life feeling you wrote about. About a year after we moved there we found out we were expecting our first child. We just couldn’t see starting our own family so far away from our parents. So at a financial loss we broke my contract and went home.

Was it the best decision? Looking back from our retirement of course there is no way to know that. But we have many wonderful memories of our time there.